SACRAMENTO, CA – The California State Assembly passed a resolution recognizing the 135th Anniversary of the signing of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 and to call on President Donald Trump to revoke his anti-immigrant executive orders.

Authored by Assemblymembers Phil Ting (D-San Francisco) and David Chiu (D-San Francisco), Assembly Joint Resolution (AJR) 14 passed with a 52-0 vote. The measure now heads to the State Senate for review.

“Today’s anti-immigrant and anti-Muslim climate isn’t unprecedented. Asian Americans see the echoes of the past in President Trump’s discriminatory and divisive executive orders today,” said Ting. “This resolution is a necessary reminder that our progress towards liberty and justice for all is fragile, and that California must stand up against leaders determined to roll back justice and equality.”

“Recognizing the travesties of our history enables us to see today’s anti-immigrant rhetoric for what it is – shameful and unacceptable,” said Chiu, whose district includes the oldest Chinatown in America. “California must be a place of freedom and hope, not oppression and racism. Let us continue to set an example of acceptance, tolerance, and unity in this great state.”

The Chinese Exclusion Act was signed into law by President Chester A. Arthur on May 6, 1882. It was the country’s first law prohibiting immigration solely on the basis of ethnicity and also denied a path to citizenship for Chinese persons for more than 60 years. The text of the Chinese Exclusion Act states “the coming of Chinese laborers to this country endangers the good order of certain localities,” which served to criminalize Chinese people who wanted to come to the United States to work.

President Trump has released several executive orders aimed at deportation and denial of entry for people from Muslim countries. Executive Orders 13767 and 13768, issued on January 25th, 2017, directs the hiring of 10,000 additional Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents, expands the categories of those who are prioritized for deportation, and calls for building a southern border wall with Mexico. Executive Order 13780, issued on March 6, 2017, suspended the entry of refugees for 120 days and sought to limit the total number of refugees entering the country.

AJR 14 is supported by Asian Americans Advancing Justice, the California Historical Society, California Immigrant Policy Center, Chinese for Affirmative Action, Coalition for Humane Immigrant Rights Los Angeles, the Council on American-Islamic Relations, and Organization of Chinese Americans Sacramento chapter.

###

Contact: Jessica Duong, tel. (916) 319-2019

Photos and information provided courtesy of the California Historical Society.

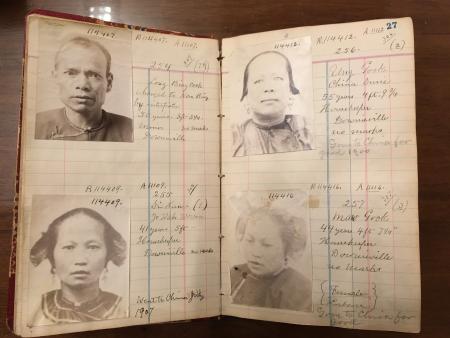

Photo 1: Immigration Officer D. D. Beatty used his 1894 journal to track Chinese immigrants in Sierra County.

Photo 1: Immigration Officer D. D. Beatty used his 1894 journal to track Chinese immigrants in Sierra County.

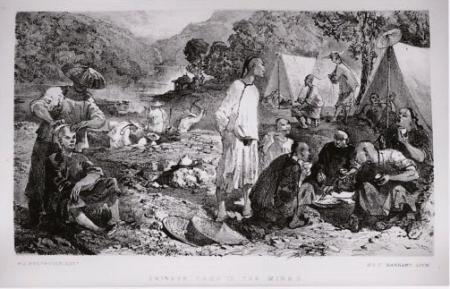

Photo 2: The Gold Rush began the heritage of Asian-Pacific Islander migration to the United States. By 1849, gold seekers were arriving from Hawaii and Australia, and Chinese began coming in large numbers in 1851–52. Before the end of the 1850s, they were the largest nonwhite group in the mining districts and already a major target of resentment and discrimination. As a result, Chinese often sought out occupations that served rather than competed against the white majority. In a largely male society, those occupations sometimes included what the nineteenth century defined as “women’s work,” including laundry, cooking and domestic service. Chinese also became low-wage manual laborers, and in that role served as the major workforce for construction of the western portion of the transcontinental railroad.

Photo 2: The Gold Rush began the heritage of Asian-Pacific Islander migration to the United States. By 1849, gold seekers were arriving from Hawaii and Australia, and Chinese began coming in large numbers in 1851–52. Before the end of the 1850s, they were the largest nonwhite group in the mining districts and already a major target of resentment and discrimination. As a result, Chinese often sought out occupations that served rather than competed against the white majority. In a largely male society, those occupations sometimes included what the nineteenth century defined as “women’s work,” including laundry, cooking and domestic service. Chinese also became low-wage manual laborers, and in that role served as the major workforce for construction of the western portion of the transcontinental railroad.

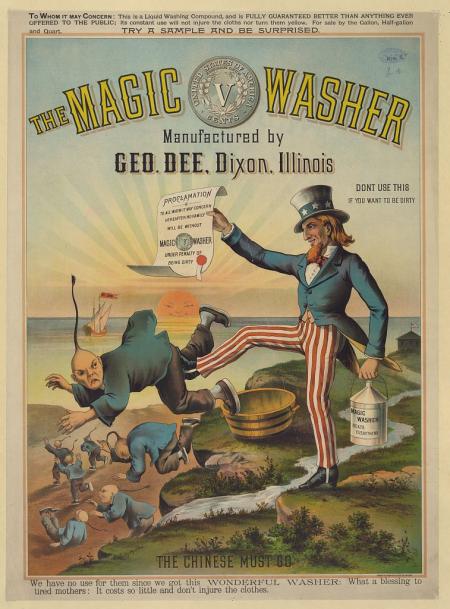

Photo 3: “The Chinese Must Go,” asserted this late-19th century ad for laundry detergent shortly after passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act. “We have no use for them since we got this WONDERFUL WASHER,” the advertisers explained, relying on widespread anti-Chinese sentiment to target a traditionally Chinese laundry business—one of many reasons why Uncle Sam should kick the Chinese out of the United States.

Photo 3: “The Chinese Must Go,” asserted this late-19th century ad for laundry detergent shortly after passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act. “We have no use for them since we got this WONDERFUL WASHER,” the advertisers explained, relying on widespread anti-Chinese sentiment to target a traditionally Chinese laundry business—one of many reasons why Uncle Sam should kick the Chinese out of the United States.

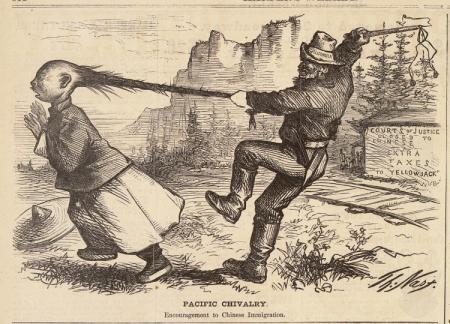

Photo 4: Chinese exclusion lasted for more than sixty years and produced a shortage of immigrant labor in California. In the 1890s, many California employers formerly dependent on Chinese labor turned to Japan as a new source of workers. Not surprisingly, by the early twentieth century, California’s well-established anti-Asian movement increasingly made Japanese immigration its primary target. Unlike 19th-century China, early-20th-century Japan was an emerging world power, and Japan’s new status produced political and diplomatic conflicts with the United States. Interethnic relations in California both reflected and reinforced these international tensions. Some influential Californians warned of a “Yellow Peril,” in which Japanese immigrants supposedly served as shock troops in a conspiracy threatening “white civilization” throughout the Pacific Basin.

Photo 4: Chinese exclusion lasted for more than sixty years and produced a shortage of immigrant labor in California. In the 1890s, many California employers formerly dependent on Chinese labor turned to Japan as a new source of workers. Not surprisingly, by the early twentieth century, California’s well-established anti-Asian movement increasingly made Japanese immigration its primary target. Unlike 19th-century China, early-20th-century Japan was an emerging world power, and Japan’s new status produced political and diplomatic conflicts with the United States. Interethnic relations in California both reflected and reinforced these international tensions. Some influential Californians warned of a “Yellow Peril,” in which Japanese immigrants supposedly served as shock troops in a conspiracy threatening “white civilization” throughout the Pacific Basin.